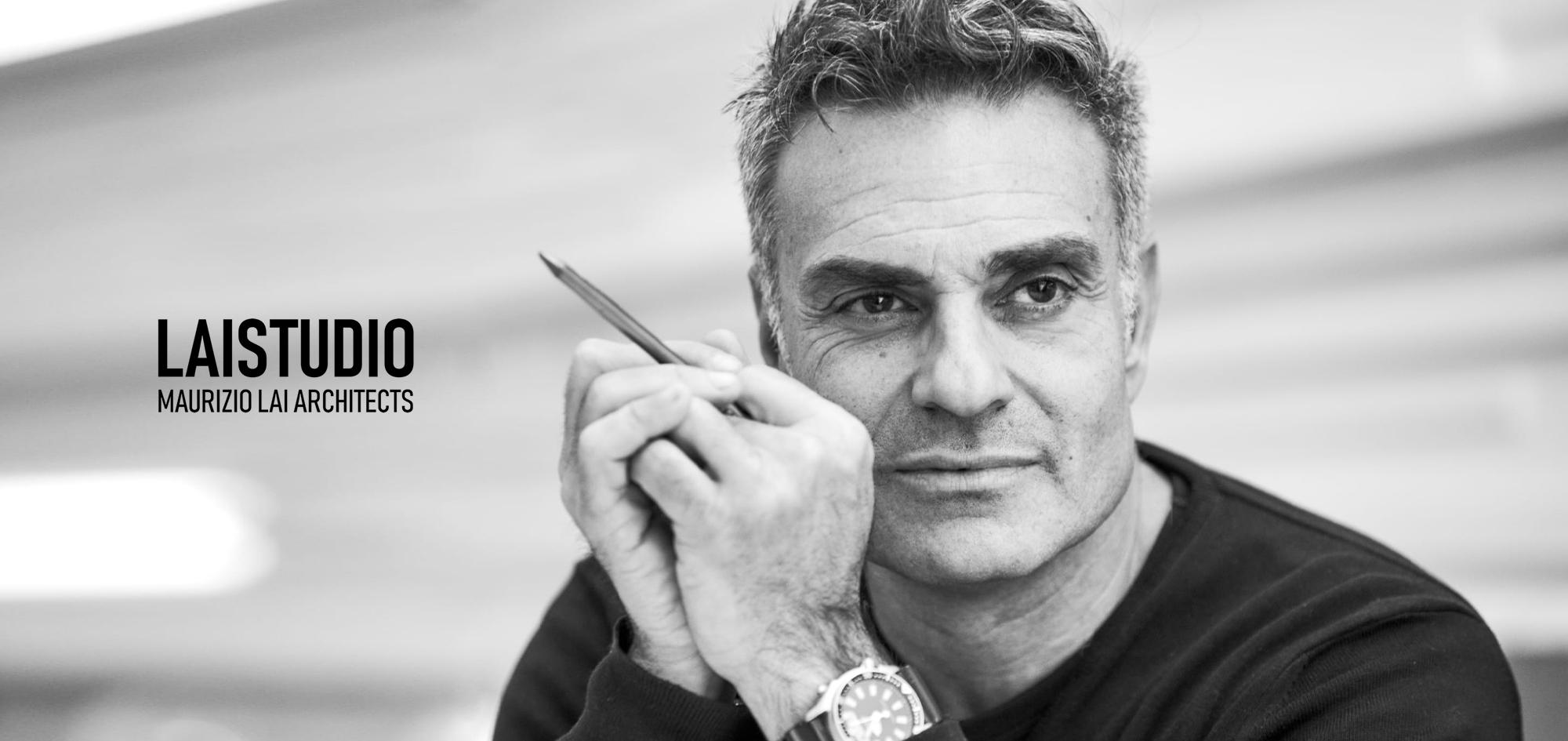

Architect, set designer, and designer, Maurizio Lai brings a distinctive signature to his work, shaped by intricate geometries and a masterful use of light. Now, he may be on the verge of a new phase of experimentation.

Maurizio, tell us your story.

My story has been a rather complex and unconventional journey. I started working at the age of twenty, while I was still studying, because I had decided to move from Venice to Milan and needed to support myself. I believed Milan would offer me more stimulation and opportunities—but at the time, I thought I’d stay only a few months. I saw it as a temporary stop. And yet, forty years later, I still feel… temporary!

My first job was changing film rolls in a fashion photographer’s studio. Shortly after, I found a similar job with another photographer, Franco Trinchinetti, who at the time had almost a monopoly on images for hairstylist catalogs. That’s where I got my first real chance to step up: he asked me to draw portraits of famous people, paired with imagined or reinterpreted hairstyles, for a book on hair design.

One day, half-jokingly, I slipped a self-portrait of myself among the celebrities. I expected a negative reaction—but instead, Franco didn’t get mad at all. In fact, he insisted on adding my name alongside Michael Jackson and Marlon Brando! I was stunned. He told me, ‘You see, now this book will travel the world, and everyone will think you’re famous too. That’s how advertising works!’That man is still a guiding figure in my life. He’s followed every step of my career with warmth and support, encouraging me in my successes and standing by me through the failures.

What was the journey from changing film rolls to founding an internationally acclaimed architecture studio?

It happened partly by chance, and partly thanks to my ability—or perhaps the courage—to seize the opportunities that came my way.

At the time, I was living in Milan: working, studying, and spending time with a group of young artists. One day, a Chinese entrepreneur asked me to design the set for a venue he had just opened, where there were cabaret performances on Saturday nights. I brought in some of those artist friends, and we began working on the project in a lively, high-energy atmosphere.

On that stage, performers who would later become household names in Italian comedy were just getting started: I Fichi d’India, Maurizio Milani, Pino Campagna, and many others. Then, one day on a train, I struck up a random conversation with two television writers. One of them was Adriano Bonfanti, a well-known TV writer. I told a “half-truth,” claiming I worked in theater. They asked for my phone number. A month later, out of the blue, I got a call: they needed someone to design the set for the pilot episode of a new show, Naturalmente bella, hosted by Daniela Rosati.

It was a delicate situation: the host had very high expectations, and I—being a newcomer—was considered a bit of a gamble. But we immediately understood each other, and that marked the start of my career as a television set designer.

I worked in that world for quite a while. But then, I felt the need for a deeper transformation. I decided to shift my professional life and fully dedicate myself to architecture. Architecture was never a fallback or a detour—it was something I had always carried within me, even if, for a long time, I approached it from the sidelines, almost unconsciously. Every time I designed a set or organized a theatrical or television space, I was already thinking like an architect: I was working with light, with volume, with flow, with the relationship between people and the environment.

I knew it was time to take the next step—to move from the ephemeral world of the stage to something more lasting, more tangible. I wanted to design spaces that would last, that could be lived in, inhabited, transformed. It wasn’t a leap into the void—it was a natural evolution.

After that I brought together my technical training, my visual and scenographic experience, and my ability to listen to and interpret people’s needs. That’s how my studio was born. Over the years, it has grown, evolved, and earned recognition on an international level.

And yet, even today, in every project I can still see that invisible thread connecting it all: graphic design, drawing, theater, photography. Different languages, yes—but they all speak of space, of identity, of storytelling.

And maybe that’s my signature: I don’t just build structures — I try to give shape to stories.

Indeed, your architectural style is very theatrical.

Over time I have developed a rather precise, recognizable style. This is another reason why I am particularly comfortable working with Chinese clients: they are attentive, concrete interlocutors, and they do not presume to impose their own ideas. They trust, and this creates the conditions for a real design dialogue. Over the years I have carried out interior projects in very different areas, always trying to maintain aesthetic consistency and functional rigor. Among the works to which I am most attached is the design of the first European vocational school dedicated to people with Asperger’s syndrome: an experience that deeply enriched me and made me reflect on the value of architecture as a tool for inclusion. More recently, I have focused a great deal on the hôtellerie and restaurant sector, areas in which the care of space directly affects people’s experience. Architecture here becomes a sensory language: welcoming, atmospheric, a balance between functionality and beauty. Today my practice has grown and has numerous collaborators.

I like to think of it as a Renaissance workshop: I provide the artistic imprint, the vision, and take overall responsibility for the projects. It’s work that demands absolute dedication and constant attention, often within tight, almost prohibitive deadlines. Every day, I try to balance the role of manager with that of artist. It’s not always easy, but it’s precisely in that tension that the project is born.

What role does figurative art play in your work, and what are your thoughts on Cinquerosso Arte?

I met Cinquerosso Arte during an event, and immediately defined it as an adventure. An exciting adventure, in which the main interlocutors are precisely the architects, called upon to act as intermediaries between the artist and the final client.

The real difficulty, however, lies in the fact that – especially when it comes to interior design – art is often reduced to a decorative element, rather than being recognized for its intrinsic, cultural and expressive value. This represents a limitation with which I am often confronted. In my work, as I said, the style is very defined, almost a formal language that is repeated and renewed.

My architectures are, in a sense, three-dimensional paintings. Each element is part of a larger design, of a precise geometric balance, in which nothing is left to chance. That is why I tend to personally attend to every detail. It often happens to me, for example, that I also design the lamps: they have to fit perfectly into the context, to help build that visual and sensory atmosphere that is part of my design idea.

This is also why, to date, there has never been much room for artistic collaborations in the traditional sense of the word. My main collaborator, after all, has always been the client: it is from him that everything starts, from his needs the perimeter of the project takes shape, and it is in that dialogue that all architecture is born. I say “so far,” because perhaps the time has come for a change.

As my history shows, my career has often taken unexpected directions, and perhaps now I am ready to open up to a new way of operating, perhaps creating synergies with other figures.